Why Our Definition of Intelligence May Be Shaped by Empire

When Enrico Fermi asked, “Where is everybody?”, he was pointing at a numerical tension. The Milky Way contains hundreds of billions of stars. Many are older than our Sun. A large fraction have planets. The universe itself is approximately 13.8 billion years old [1].

Given enough time, even a civilization traveling at a small fraction of the speed of light could, in principle, spread across the galaxy [2]. If intelligent life is not extraordinarily rare, then someone should have left traces — probes, megastructures, artificial signals, something detectable [3].

And yet, the sky is silent.

That silence is called a paradox. But perhaps it is not astrophysics that needs rethinking. Perhaps it is the assumption hidden inside the question.

The Assumption

The Fermi Paradox quietly assumes that intelligence expands.

It assumes that once a species develops advanced technology, it will:

- Seek new territory.

- Extract new resources.

- Spread beyond its home world.

- Leave visible marks.

In other words, it assumes that intelligence behaves like empire.

That assumption feels intuitive because it mirrors one of the most visible patterns in human history: expansion across oceans, consolidation of trade routes, colonization of distant lands.

But intuition is often just familiarity. And familiarity can be local.

When the Aliens Arrived

I am Moluccan. My family is part of the community that arrived in the Netherlands in 1951 after the dissolution of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL). Around 12,500 Moluccan soldiers and their families were transported to the Netherlands, officially on a temporary basis [4]. They were told they would return once the political situation in the Moluccas stabilized after the proclamation of the Republik Maluku Selatan (RMS) in 1950 [5]. That return never came.

But centuries earlier, something else arrived.

European ships appeared on the horizon of the Moluccan islands — drawn not by abstract curiosity, but by spices. Cloves and nutmeg grew naturally in the islands and nowhere else. In early modern Europe, these spices were immensely valuable [6].

Rarity functioned as a signal. And the signal was received.

The Portuguese arrived first. The Dutch followed. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) consolidated control over the spice trade in the 17th century, enforcing monopolies that reshaped local political and economic systems [7].

From Europe, this was expansion — exploration, commerce, global integration. From the islands, something different had occurred.

Aliens had arrived.

They were technologically different — ocean-faring, heavily armed, backed by distant economic systems. They reorganized local life around extraction and monopoly. What had been locally embedded networks became nodes in a global trade system.

The spices were not a radio transmission. But they functioned like one. They signaled value. And value attracts power.

Signals and Consequences

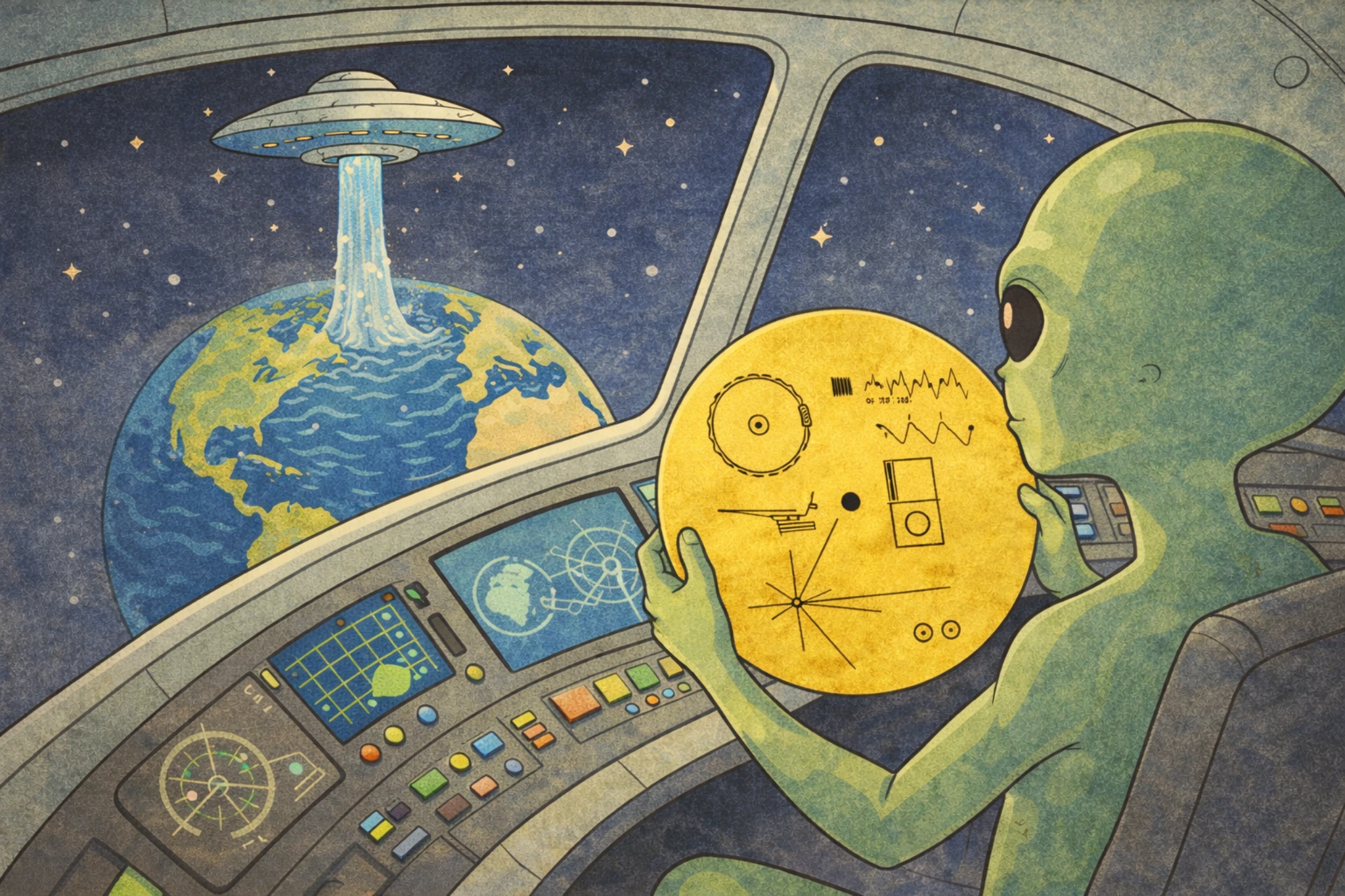

In 1974, humanity transmitted the Arecibo message — a structured radio signal aimed at the globular cluster M13, encoding basic information about mathematics, chemistry, and ourselves [8].

In 1977, Voyager 1 departed Earth carrying a golden record — sounds, images, greetings, and a map indicating our location relative to pulsars [9].

We sometimes describe these acts as hopeful gestures. We frame them as the natural curiosity of an intelligent species.

But they are also signals.

They say:

- Here we are.

- Here is our chemistry.

- Here is where to find us.

History makes me cautious about signals of value.

The Moluccas did not broadcast their location. But scarcity within global trade networks made the islands visible. Spices were the Arecibo transmission of their time.

The result was not mutual curiosity alone. It was asymmetry.

Intelligence and Expansion

The Fermi Paradox assumes that if intelligent civilizations exist, they will behave as expansionist powers. But expansion is not synonymous with intelligence. It is one possible expression of capability.

The Dutch East India Company expanded not because expansion is written into the laws of the universe, but because competition and economic incentives rewarded monopoly. Expansion was a strategic response to perceived opportunity.

In cosmic reasoning, we often imagine habitable planets as rare nodes of value — like spice islands scattered across a vast ocean. We imagine advanced civilizations drawn toward them, harvesting resources, colonizing new worlds.

But this imagination is shaped by history. It assumes that intelligence is inherently extractive. What if it is not?

Life Is Mostly Quiet

Life on Earth has existed for about 3.5 billion years [10]. For almost all of that time, it was microbial. Complex multicellular ecosystems developed without attempting interstellar travel.

Even human technological civilization — the phase in which we emit detectable radio signals — spans barely a century [11]. Our loudness is recent. We assume it is permanent.

But perhaps civilizations have loud phases — bursts of technological growth and outward signaling — that are brief relative to cosmic timescales. Perhaps many collapse. Perhaps others stabilize and deliberately reduce their footprint.

A civilization that optimizes for sustainability may:

- Minimize waste heat.

- Use directional, low-leakage communication.

- Avoid large-scale astroengineering.

- Recognize the risks of broadcasting into the unknown.

From interstellar distances, such civilizations would be indistinguishable from silence. The galaxy could be full of life and appear empty.

Rethinking the Paradox

When European ships came to the Moluccas, they were drawn by resources. They reorganized the islands around extraction. The expansion was technologically sophisticated and economically rational — from one perspective.

From another perspective, it was invasive.

We would experience it as power. The Fermi Paradox asks why no one has come. But perhaps the more relevant question is: why do we assume that coming is inevitable? Why do we assume that intelligence must cross every horizon it can?

History suggests that expansion is not the endpoint of intelligence. It is a phase. Empires rise and fall. Trade networks reconfigure. Communities endure long after expansionist systems collapse.

The Moluccan story did not end with the arrival of European ships. It continued — through colonial rule, through displacement in 1951, through generations preserving identity in a different land [4].

Endurance can be quieter than conquest. But it may be deeper.

The Silence Reconsidered

The silence of the stars may not indicate absence.

It may indicate that intelligence does not inevitably become empire.

Perhaps the most advanced civilizations learned something we have not yet fully learned — that expansion is not always wisdom, that signaling carries risk, that sustainability matters more than visibility.

Our spices once functioned like a beacon in global trade networks. Our radio waves now function like one in cosmic space.

The Fermi Paradox assumes that intelligent life spreads across the galaxy the way ships once spread across oceans. But perhaps that assumption reflects our history more than it reflects the universe. Maybe the real question is not “Where is everybody?”

Maybe it is: Why do we expect intelligence to behave like the ships that once appeared on our horizon?

Sources

- Planck Collaboration (2018). Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters.

- Hart, M. H. (1975). "Explanation for the Absence of Extraterrestrials on Earth."

- NASA Technosignatures Workshop Report (2018).

- NIOD Institute – Moluccan KNIL relocation (1951).

- Republic of South Maluku (RMS) historical context.

- Milton, G. (1999). Nathaniel’s Nutmeg.

- Gaastra, F. S. (2003). The Dutch East India Company: Expansion and Decline.

- The Arecibo Message (1974).

- NASA JPL – Voyager Golden Record (1977).

- Schopf, J. W. (2006). Fossil evidence of early life on Earth.

- SETI Institute – Radio signal detectability.